‘It takes a woman to think up a design idea that other women have been wanting for years.’

LUCIENNE DAY. TEXTILE DESIGNER

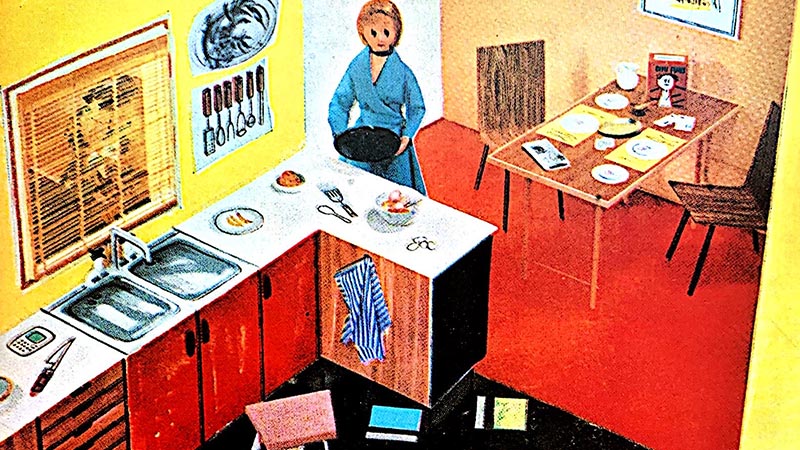

FOLLOWING the bleak austerity of World War Ⅱ, engineering brilliance and creative energy once deployed for wartime necessities became focused on domestic design. Colour and pattern were introduced to household goods as innovations in interior product design flourished. Consigned once more to the domestic sphere after the relative freedom enjoyed during the exigencies of war work, women elevated the kitchen beyond a place of simple utility, for some previously the domain of servants, to become the heart of the home. Here, the housewife directed her energies to incorporate style and novelty into the epicenter of her domestic empire. The evolving domestic aesthetic incorporated a feminine version of Modernism, and expendable ephemera such as small kitchen accessories in the form of tableware and tea towels allowed her a freedom of expression that was otherwise lacking in the narrowly prescribed life of the 1950s housewife. Under her dominion, the kitchen became a social space and an arena for display, with the division of labor sharply defined between the sexes.

New scientific materials usurped the role of traditional surface finishes. Seats were glossily vinyl covered, while tables and cupboard fronts were transformed with plastic laminates, such as Con-Tact, a sticky-backed vinyl film developed in 1954, or the more durable Formica- each flaunting brighter colors and washable, stain-resistant surfaces. These allowed an overall scheme of color and pattern in which the tea towel played an integral part. Stylization and abstraction infused the prevailing aesthetic. The result was an inflection of both scientific modernity and the high culture of international modern art, with forms vaunted by sculptors like Gabo, Hepworth, Arp and Picasso subliminally influencing the domestic landscape. Patterns took on dynamic asymmetrical forms, such as the pointed boomerang, a symbol of movement and flight, or the artist’s palette with its blobs of vibrant color. Scientific advances provided the molecule as inspiration, as did skeletal plant forms and the work of artists that included Alexander Calder and Joan MirÓ.

These influences came to fruition in both textiles and ceramics, such as Terence Conran’s Chequers. This was developed in 1957, based on a design Conran originally created in 1951 for the textile manufacturer David Whitehead. Enid Seeney’s Homemaker tableware for Ridgway Potteries, designed in 1955, was decorated with everyday contemporary items. Seeney incorporated a representation of a chair designed by Robin Day, exemplifying the cross-fertilization and integration of design ideas across a broad spectrum of products. When the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) was founded in 1947 it emblemized the new panorama of post-war optimism and creativity in the single word ‘contemporary’, bridging all sectors – including art, architecture, product, graphic design and textiles. In this period textile design pioneers were legion, including Marian Mahler, Tom Mellor, Jacqueline Groag and Lucienne Day, who produced several designs for the influential Festival of Britain in 1951. This exhibition was staged to promote the most exciting and progressive in new British design. Day’s influential Calyx design retailed through Heal’s Fabrics and resulted in a plethora of copies. Technical developments, for example, the use of automatic screen printing, reduced the cost and fuelled the introduction of new patterns to the marketplace, enabling these designs to be accessible to a wider audience.

Although wartime food rationing continued until 1954, representations of utopian domesticity and fanciful consumption -from flowering geraniums in terracotta plant pots or trailing ivy over a trellis, to fruit in bowls, wine glasses, jugs, vases and kitchen utensils-all featured on the contemporary tea towel. In this way, daily minutiae were to be seen as a celebration and resurrection of the importance of the home and the stability of family households.

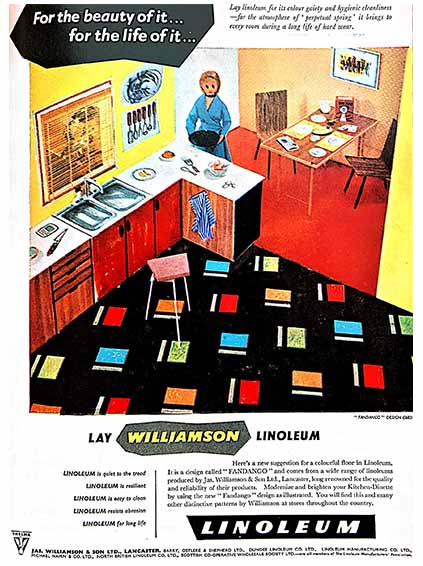

Above: At the risk of spoiling the broth, Lucienne Day designed Too Many Cooks in 1959 for Thomas Somerset’s Fragonard range. It gained a Design Centre Award in 1960 and was a popular commercial product, offered in a variety of colorways.

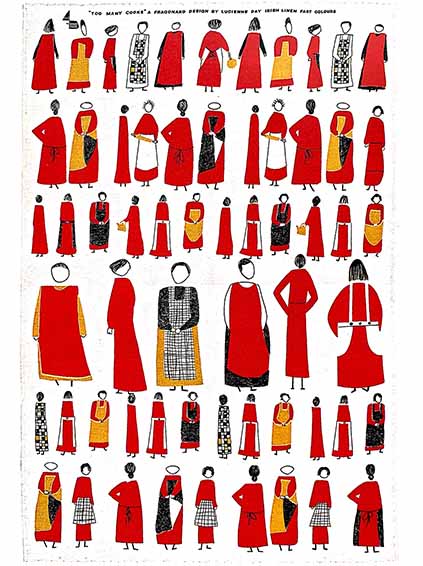

Above left: One of three designs from 1959 by Lucienne Day for Fragonard that gained a Design Centre Award, Black Leaf is a very spare, two-color, two-screen figurative composition that comes close to pure abstraction.

Above right: On and between bold bands of warm tones, Lucienne Day superimposes and interlays informal natural images in black, in the form of hand script and physical offprints from herbs. Bouquet Garni for Fragonard won both a Design Centre Award and a Gold Medal at the California State Fair in 1960.

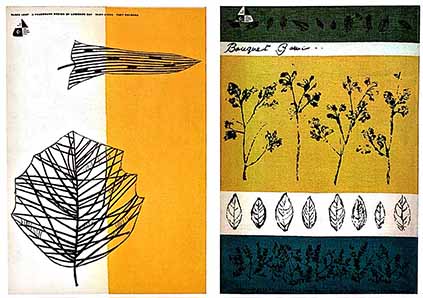

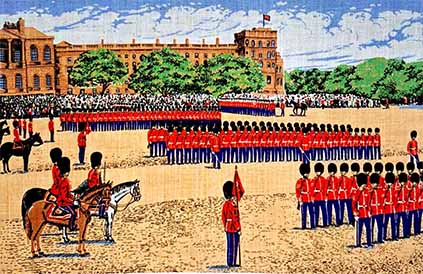

Above: Trooping the Colour from Ulster Weavers is a study in obtaining optimum ‘realism’ from a finite number of screens. Each of the separated colors is distributed into as many figurative components as is viable for legibility. Overprint tones are also exploited to imply a wider color gamut, although the effect remains graphically naïve.

Above: Quartered to do justice to four emblematic national edifices- St. Paul’s Cathedral, Westminster Abbey, Buckingham Palace and the Tower of London- this pure linen memento of the 1953 Coronation enlists a cornucopia of elemental regalia to celebrate the occasion The crown of St. Edward and the Gold State Coach are elegantly rendered in the midst of garlanded swags of ribbon, flags and regal flora.

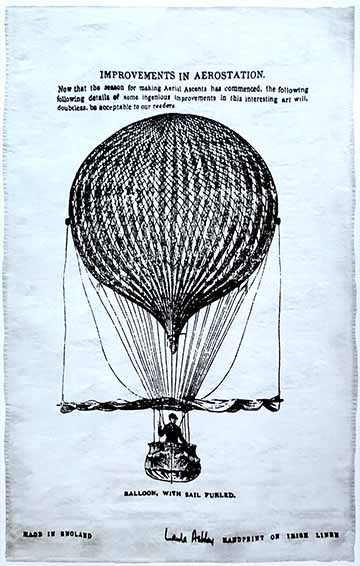

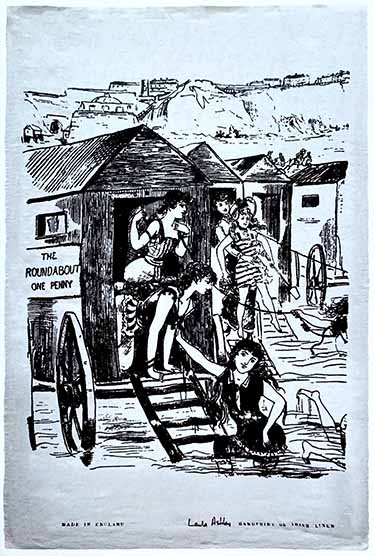

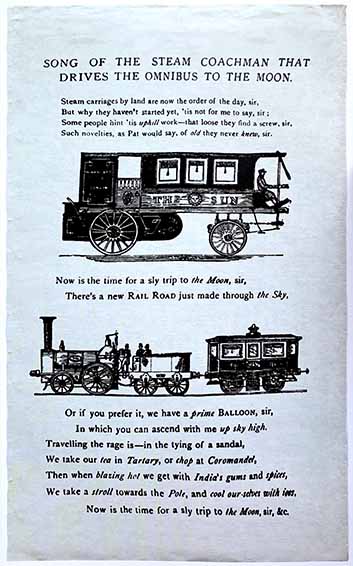

The Laura Ashley company was founded in 1953, with Laura Ashley and her husband Bernard printing by the silkscreen process in their London flat. The image is lifted from the Victorian ballad monger and pamphleteer, James Catnatch of Seven Dials, London.

Above: One of a series of Laura Ashley tea towels based on Victorian advertisements and playbills that recall with mild irony the nostalgic pleasures of simpler times. The single-color images are silk-screened directly onto the cloth by hand.

Above: James Catnatch, a London printer, conducted his trade in chapbook broadside ballads over several decades, working until his death in 1841 with woodcut artists such as Thomas Bewick. Laura Ashley found his publications a rich source for

Her early tea-towel prints.

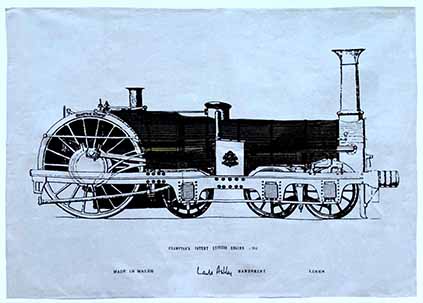

Above: Thomas Crampton exhibited his patented “Liverpool’ Express Steam Engine in the 1851 Great Exhibition to extensive international acclaim, becoming the byword for express travel across Europe. This engraving from his patent application adorns an early Laura Ashley tea towel.

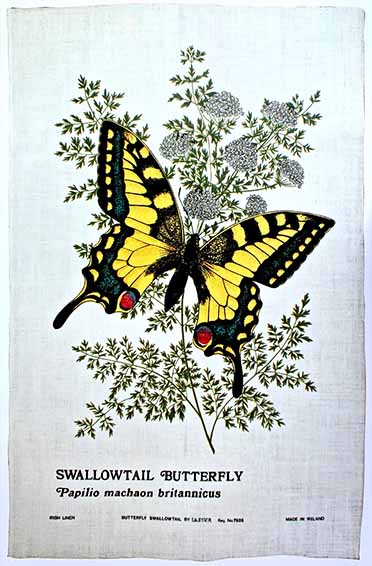

Above: Both old and new world swallowtails are habitual denizens of wild carrot,

visiting through all stages of their metamorphosis. Here Ulster Weavers

illuminates this butterfly with the precision of a lepidoptery guide.

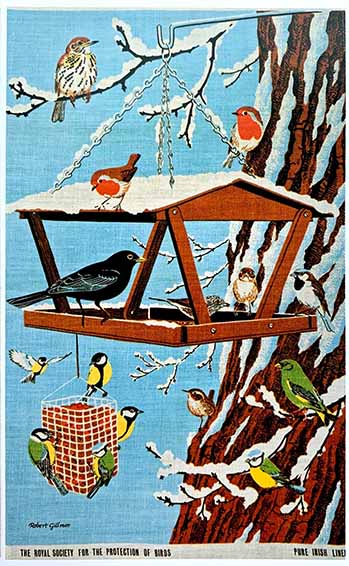

Based in Norfolk, Robert Gillmor is a founder member and former president of the Society of Wildlife Artists. The RSPB commissioned this species compendium of over-wintering British birds.

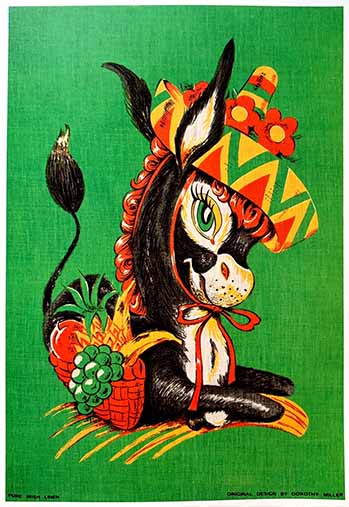

Above: During the 1950s idiosyncratic subject matter and whimsical imagery presaged the use of popular culture as art form later seen in the work of the 1960s pop Artists. This doe-eyed transgression in donkey form by Dorothy Miller caters to the Costa package sub-culture.

Above: The poodle had a particular place in 1950s iconography, representing European ‘sophistication’, However, Dorothy Miller introduces kitsch into the kitchen with a poodle puppy adorned in ribbon bows sitting in a chrysanthemum pot.

《the art of the tea towel》

Marnie Fogg