Just as the programme serves as souvenir of a play, a lasting memory of the visit to the theatre, so, for many years, the tea towel was a vital part of a visit to a National Trust property. Millions of linen cloths were sold in Trust shops nationwide and taken home. Many were pinned or hung on the kitchen wall, a reminder of each of the pieces that make up the richest collection of property ever amassed in the country.

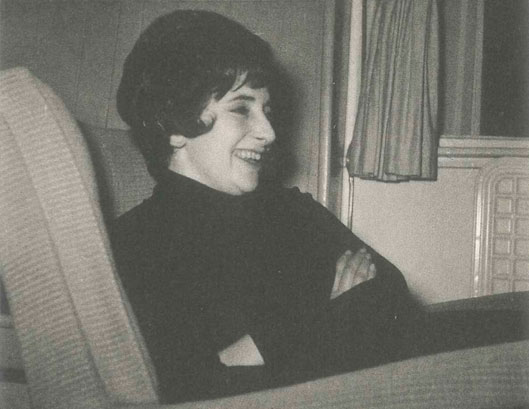

By far the majority of these were designed by one woman whose background 一 as the child of Jewish immigrants from Russian Poland – was as far from the patrician ways of the twentieth-century National Trust as could be imagined. Pat was the youngest daughter of Motel Albeck, a furrier. He and his wife Sarah had arrived in London’s East End in 1908 leaving behind their lives and families in the shtetl of Zarimbe near Warsaw. They then moved to Hull, where Pat was born.

Motel, now renamed an anglicised Max, was quickly established in a new business and sent the three eldest daughters to university. However with modest results at School Certificate, Pat was quickly dispatched to the Hull School of Art where she shone. Winning, in 1950, a place at the Royal College of Art, she left for London. There she met her husband, Peter Rice, a painting student, and from then on their lives were utterly devoted to design until their deaths in 2015 and 2017. At the RCA, Pat had studied in the textile school and worked in fashion and furnishing design throughout the 1950s and ‘60s, but a chance meeting at a dinner added a further dimension to her work.

Pat and Peter had moved from South Kensington (where they had settled while at the RCA) to Chiswick Mall in 1963. In part the product of the intrusive construction of the Great West Road the year before, this ribbon of variegated houses was inadvertently isolated from the rest of grittier west London and became an oasis of Thames-side quiet. It had already been established as an artistic enclave, and foremost amongst its residents at the time were the painters Mary Fedden and Julian Trevelyan. As close neighbours they instantly became friends of Pat and Peter. An introduction to Mary’s cousin Robin, who was historic buildings officer at the Trust, led to a discussion about the possibility of Pat producing some “illustrated dishcloths for the tables/ The tables were the low-key predecessors of the later ubiquitous National Trust shops, simply a table in the hall where some postcards were sold along with the property guidebooks. Pat was delighted and there began a fifty-year productive relationship.

If the tea towels defined Pat Albeck for many people it was conversely the case that her designs exemplified the extent and the tone of the Trust. Perhaps they even served in some way as a precursor to the more accessible and egalitarian organization it was having so much difficulty in becoming. Pat’s combination of informed acute observation and bold schematic design produced a representation of the houses, parks, kitchens and gardens of the Trusts estate that was itself a welcoming and familiar introduction to what had been the privilege of the few.