‘The trusty tea towel is good -not the grubby rag that has been hanging on the door for a week but a crisply linen one. I love tea towels. I love having a constantly high pile of them in the cupboard and I really like them to be pressed.’

— RITA KONIG, INTERIOR DESIGNER AND JOURNALIST

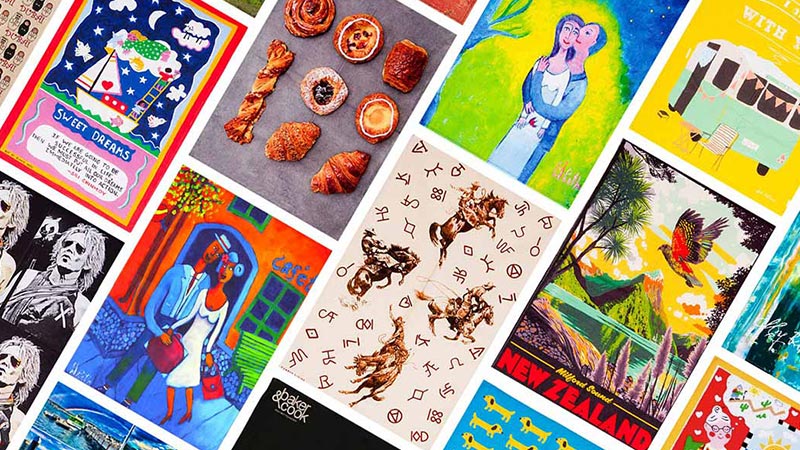

ANT ELEVATION of the humble tea towel to the status of cultural icon may seem a bold assertion but as a metaphor conveying totemic aspects of domesticity stability and design creativity it has attracted nuanced contexts that deserve reflection and a level of celebration.

Since its emergence as a manufactured artefact during the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century, the mass-produced tea towel has provided a microcosm of domestic iconography-far exceeding the confines of its very obvious utility, It has become an essential memento of leisure spending, purchased From museums, country-house properties and holidays, as well as commemorating significant national events – a royal wedding or jubilee, encouraging an entire community to share the experience.

Most signi6cantly tea towels have operated as vehicles for a host of design movements, acting as a medium supporting all the characteristics of a broader graphic style, from the artwork of designers such as Lucienne Day to that of Pat A1beck, renowned for her work for the National Trust.

This book charts the evolution of the tea towel from the linen cloth-frequently embroidered in the 1 8th century to match the table linen and initially used to keep the teapot warm-to an essential styling accessory for contemporary kitchens, produced by practitioners as diverse as iconoclastic fashion designer Matty Bovan and printmaker Angela Harding. It is a form of democratic art, a vehicle for artists and printmakers to disseminate their work to a wider audience, outside the curated work of a gallery. The tea towel may also offer a disruptive comment on society matching the poster and T-shirt as an effective and powerful form of sloganeering.

The canvas was initially linen, a natural fibre or fabric made from the cultivated flax plant, Linum usitatissimum. Prized for its softness and stronger when wet than dry it has a smooth surface, making the final fabric lint-free. Early 20th-century household manuals occasionally called them glass towels. Progress in manufacturing textiles has changed the materials used to make tea towels to less expensive fibres, particularly cotton, or a mix of linen and cotton called Linen Union. The Linen Union tea towel is a 55 per cent linen, 45 per cent cotton mix, bleached white. It offers a more open weave and is popular within the heritage market. Sizes are generally uniform, 78 × 48cm (30314 × 19in), creatinga print area of 72 × 42cm (28 × 16 · vzin). During the latter part of the1990s, advances in digital printing and dye development-where an image can be sent directly from a computer to the cloth-became an option to replace the labour-intensive process of conventional silk-screen printing, where the cost of short runs is prohibitive due to the inevitable investment in colour separations, screen preparation and production downtime.The new technology allows the freelance designer and producer to experiment without too much initial outlay and also enables the ready exploitation and manufacture of heritage and archival subject matter from vintage posters and so on, such as those sold at Heal’s.

By the 19th century and the early to mid-20th century, a glass towel or tea towel would most likely have been a striped or checked cloth. The first commercially successful printed tea towels were pioneered by Swedish-born designer Astrid Sampe in 1955. Trained at the Swedish University of Arts, Crafts and Design(Konstfack)in Stockholm, and later at the Royal College of Art in London, in 1937 she started working as a designer at Nordiska Kompaniet, and a year later became the manager of the newly created NK Textile Studio(Textilkammaren). She revolutionized the traditional use of linen with the collection Linnelinjen(Linen Line’), a range of textiles that included tea towels, launched at the Helsingborg Exhibition in 1955.The most influential of these was inspired by Astrid Sampe’s Persson’s Spice Rack, dedicated to the ceramist Signe Persson Melin, who, in the early 1950s, made a series of ceramic spice jars with cork heads. The design continues to remain a bestseller. Astrid’s personal ethos, “Order is Freedom’, is reflected in the graphic symmetry and straight lines of her aesthetic and set the template for the designs which were to follow: versions of various kitchen paraphernalia, storage jars, utensils, and items of food such as fish and fruit. Shortly afterwards, Lucienne Day was commissioned by the Irish linen company Thomas Somerset&Co. of Belfast and their subsidiary Fragonard Ltd to revitalize a flagging Irish linen business, resulting in a series of groundbreaking and commercially successful designs that secured the place of the tea towel firmly at the high end of design.

The highly decorative printed tea towel flourished during the 1950s and ’60s-a period during which printed textiles burgeoned following the era of wartime austerity. This was kick-started by the Festival of Britain in 1951, and flourished during the following decade when print, illustration and graphics were a pervasive presence in modern life. During periods when minimalism was the prevailing aesthetic, the tea towel was chosen for its utility, more often a plain cloth with jacquard text proclaiming ‘glass cloth’, woven into a blue or red stripe, or the traditional checked waffle weave. However, there is now a new interest in the artistic and commercial potential of the printed tea towel, evidenced by the involvement of designers, artists and printmakers in the genre.

《the art of the tea towel》

Marnie Fogg