‘The best shabby chic is not created but an expression of how you are by nature. Natural grace and style helps.’

MIN HOGG.

FOUNDING EDITOR OF THE WORLD OF INTERIORS MAGAZINE, 1981

INCREASINGLY known as the ‘ designer decade’, a newly expanding consumer culture during the 1980s bought into the concept of ‘lifestyle’ marketing, in which the domestic interior played a major part. It was an era of conspicuous consumption and heralded the emergence of the ‘yuppie’ -the Young, Upwardly mobile (or Urban) Professionals satirized by American journalist Tom Wolfe in his 1987 novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities.

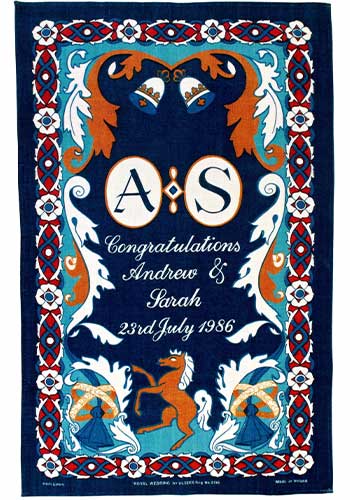

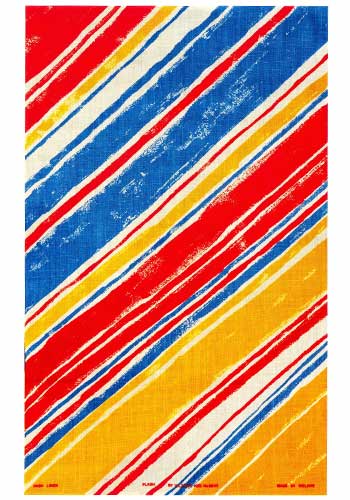

1980s tea towel

Open-plan kitchens became popular, like walls and doors that traditionally separated distinct functional areas, such as the living room, dining room and kitchen disappeared. It was a concept designed for family living, with the introduction of sofas and rugs and large, all-purpose tables for family dining. Grander, country-house-style kitchens, a throwback to the 18th century, became prevalent with bespoke, hand-crafted units. An essential component was the AGA range cooker, particularly with the introduction of the first electric model in 1985, which featured a useful bar across the front from which to hang tea towels. It was an aspirational, aristocratic look that resulted in grandiose designs – large-scale floral bouquets, elaborate gilding and twisted scroll forms on chintz. These appeared in urban kitchens, as well as in-country homes. The British company, Warner, of designer Eddie Squires, produced the ‘Stately Homes’ collection, including patterns such as Marble Hall. The trompe l’oeil effects of traditional decorative accessories, such as passementerie, appeared in prints including London Tassels by Mandy Martin in 1987. Laura Ashley’s previous preoccupation with diminutive floral designs evolved into a grander decorative idiom of the country-house look, with large-scale designs and more formal patterns.

The first publication of the influential magazine Interiors appeared in November 1981, founded in the UK in London by Kevin Kelly, with Min Hogg as editor. In 1983 the magazine was bought by Condé Nast and it began publishing internationally under the name The World of Interiors. The magazine promulgated the new obsession with decoration, paint effects such as faux marble and rag-rolling, swagged curtain pelmets and Roman blinds, which even appeared in the kitchen. Historic houses and stately homes provided a cornucopia of inspiration; those owned by the National Trust were open to the general public and became a leisure destination throughout the decade. Pat Albeck continued to design, not only tea towels but also a coordinated range of products, such as table linen, kitchen textiles and ceramics for the National Trust gift shops.

In contrast, at an international level, an urban style of vibrant geometrics was created in 1981 by the Italian architect and designer Ettore Sottsass, who founded the design collective Memphis. Named after the Bob Dylan song, ‘Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again’, it was a reaction to the Bauhaus mantra of ‘Form follows function, which shunned the purely decorative Sourcing 1950s kitsch, Art Deco and 1960s pop culture, their unconventional and playful use of primary colors, and uninhibited patterning and texture introduced the notion of Postmodernism to interior design. This theoretical outlook utilized period styles and references, treating the past as one huge antique supermarket. This broke the established rules about style and incorporated the notion that ‘anything goes, as pattern provided a transformative role on domestic objects.

Timney Fowler, a partnership forged by artist Sue Timney and graphic designer Graham Fowler in 1980, introduced a Neoclassical collection of bold black-on-white and white-on-black images that proved enormously influential on the domestic interior market. Playfully deconstructing historical motifs in a way that retained all the grandiosity of the original but none of the representations of engravings of classical statues and architectural fragments was particularly aligned with the consuming interest in the ‘designed interior’.

In contrast to the swags and swathes of the designer-driven kitchen was the popularity of ‘ shabby chic’, a term coined by Min Hogg that encompassed faded chintz, painted furniture worn to expose the timber beneath, simple fabrics such as mattress ticking and pastel linens and painted cabinets. Such informality, evocative of cozy kitchens, well-loved household objects and mismatched china successfully tapped into a desire for informality-kitchen suppers rather than dinner parties.

Ulster Weavers follow their template for commemorative royal tea towels. Royal occasions-such as weddings – were of considerable commercial significance and resulted in a profusion of ephemera, including tea towels.

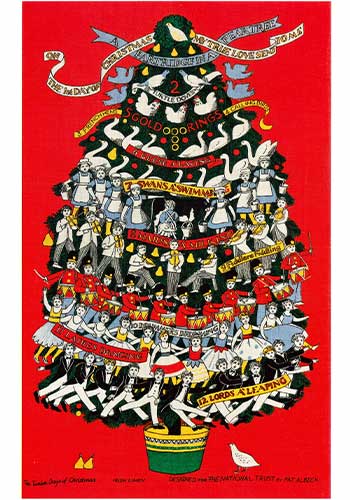

A cheerful addition to the Christmas kitchen, designed by Pat Albeck for the National Trust. The cleverly constructed illustration of a Christmas tree is festooned with the prolific gifts from the seasonal song, ‘The Twelve Days of Christmas’.

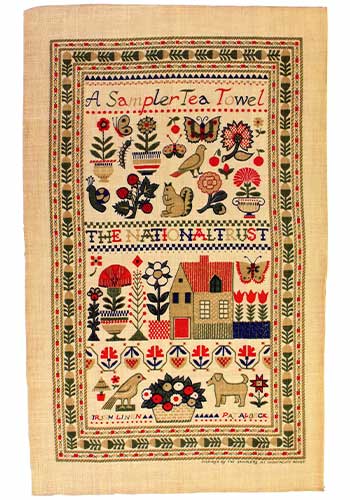

Pat Albeck was inspired by the samplers at Montacute House, a late Elizabethan mansion in South Somerset for this design for the National Trust. Samplers derive their English name from the French essamplaire, loosely meaning ‘ to be copied’.

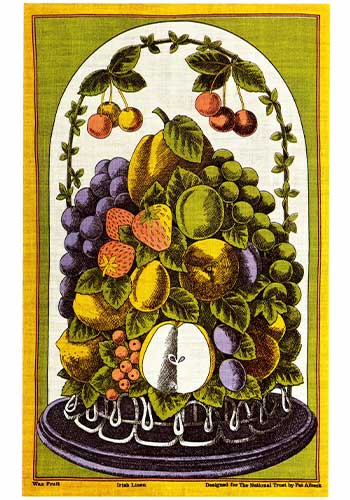

Printed on Irish linen and designed for The National Trust by Pat Albeck, Wax Fruit acknowledges the prevailing interest in Victoriana. Various species are displayed in a glass dome, a popular decorative device in the 19th century more usually containing specimens of taxidermy.

Created by Ulster Weavers at the time of Bananarama, Flashdance and Jane Fonda’s Workout video, Flash presents a dégradée sports stripe on a strong diagonal to create a sense of dynamic movement fit for a yuppie kitchen.

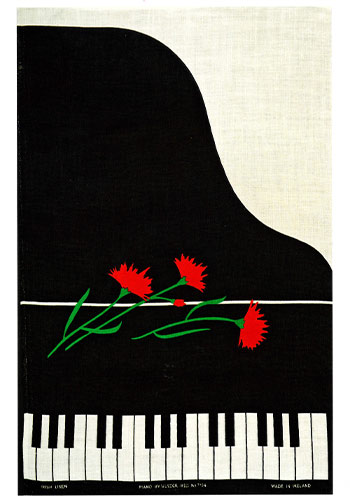

Designed during the cocktail era by Ulster Weavers, the spray of carnations cast over the surface of a glossy grand piano purports to convey the ‘80s sophistication and decadence conveyed in a Jack Vettriano poster of a piano bar.

《the art of the tea towel》

Marnie Fogg